Engineers from Rice University in Houston, Texas, United States are developing ionic water treatment technology that saves money and energy by selectively removing only hazardous contaminants and ignoring those that are harmless. The platform technology could be used to treat drinking water and wastewater from industrial applications like oil and gas wells.

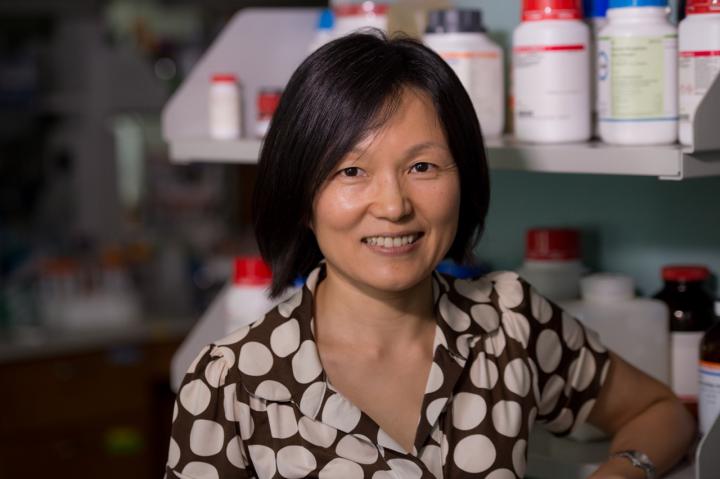

The Rice lab of engineer Qilin Li who is leading the study said, “Traditional methods to remove everything, such as reverse osmosis, are expensive and energy intensive. If we figure out a way to just fish out these minor components, we can save a lot of energy.”

At the heart of the system is a set of novel composite electrodes that enable capacitive deionization. The charged, porous electrodes selectively pull target ions from fluids passing through the maze-like system. When the pores get filled with toxins, the electrodes can be cleaned, restored to their original capacity and reused.

“This is part of a broad scope of research to figure out ways to selectively remove ionic contaminants,” Li said.

Li, who is a professor of civil and environmental engineering and of materials science and nanoengineering, added, “There are a lot of ions in water. Not everything is toxic. For example, sodium chloride (salt) is perfectly benign. We don’t have to remove it unless the concentration gets too high. For many applications, we can leave non-hazardous ions behind, but there are certain ions that we need to remove,” she said.

The new technology has the potential to be used to remove arsenic from drinking water wells, lead and copper from water that is piped, and in industrial applications where there are calcium and sulfate ions that form scale buildup.

The proof-of-principal system developed by Li’s team removed sulfate ions, a scale-forming mineral that can give water a bitter taste and act as a laxative. The system’s electrodes were coated with activated carbon, which was in turn coated by a thin film of tiny resin particles held together by quaternized polyvinyl alcohol, an inexpensive hydrophilic semi-crystalline polymer. When sulfate-contaminated water flowed through a channel between the charged electrodes, sulfate ions were attracted by the electrodes, passed through the resin coating and stuck to the carbon.

“The true merit of this work is not that we were able to selectively remove sulfate because there are many other contaminants that are perhaps more important,” she said. “The merit is that we developed a technology platform that we can use to target other contaminants as well by varying the composition of the electrode coating.”

The Rice team is developing coatings for other contaminants and working with labs at the University of Texas at El Paso and Arizona State University on large-scale test systems. Zuo said it should also be possible to scale systems down for in-home water purification.

Details about the new technology are published in the American Chemical Society journal Environmental Science & Technology.