The cholera-causing bacterium, Vibrio cholerae, is commonly found in aquatic environments, such as oceans, ponds, and rivers. There, the bacterium has evolved formidable skills to ensure its survival, growth, and occasional transmission to humans, especially in endemic areas of the globe.

One of the ways the pathogen defends itself against predatory aquatic amoebas involves “hitchhiking” them and hiding inside the amoeba. Once there, the bacterium resists digestion and establishes a replication niche within the host’s osmoregulatory organelle. This organelle is essential for the amoeba to balance its internal water pressure with the pressure exerted by the environment.

In a new study, led by Melanie Blokesch at the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne, in Switzerland, in collaboration with the BioEM facility headed by Graham Knott, has deciphered the molecular mechanisms that V. cholerae uses to colonize aquatic amoebas.

The researchers demonstrated that the pathogen uses specific features that allow it to maintain its intra-amoebal replication niche and to ultimately escape from the succumbed host. Several of these features, including extracellular enzymes and the ability of the organism to move independently using metabolic energy, are considered minor virulence factors as they also play a role in human disease.

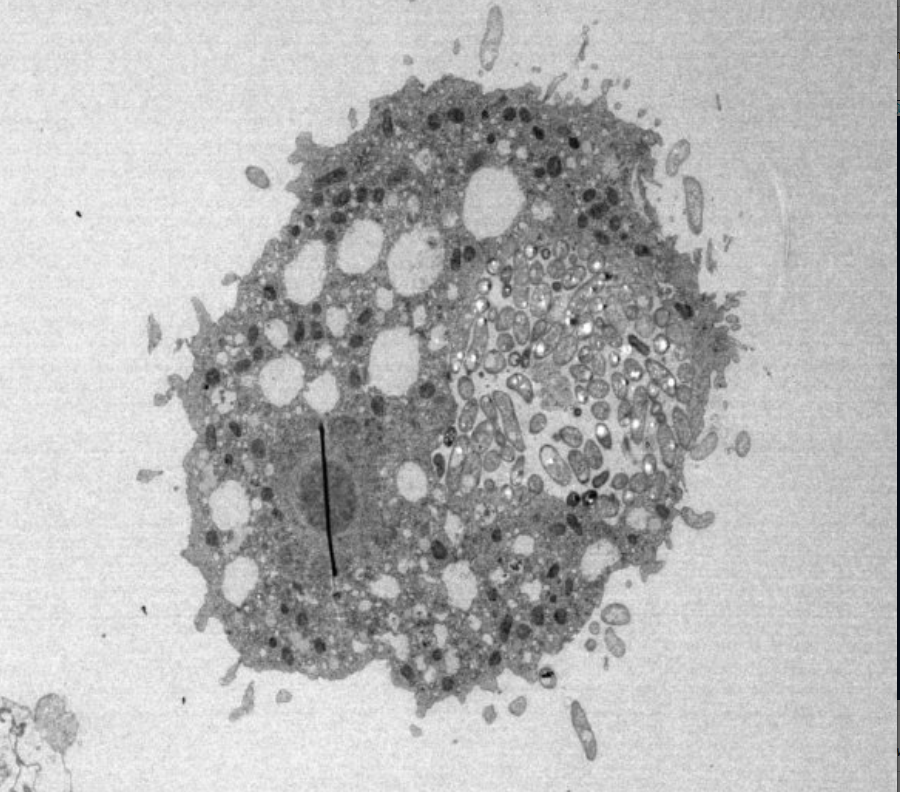

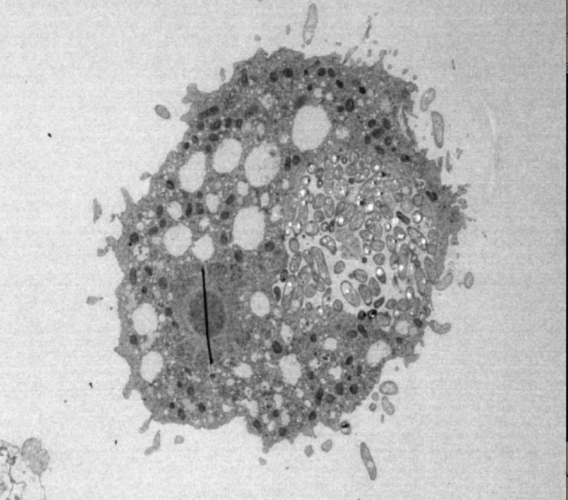

Credit: Blokesch lab and BioEM facility (EPFL).

The study suggests that the aquatic milieu provides a training ground for V. cholerae and that adaptation towards amoebal predators might have contributed to V. cholerae‘s emergence as a major human pathogen.

“We are quite excited about these new data, as they support the hypothesis that predation pressure can select for specific features that might have dual roles—in the environment and within infected humans,” said Blokesch.

Cholera is not a common disease in Canada. In Ontario, an average of one case per year is reported and all cases have been exposed to cholera in a country where cholera is endemic; however, in March 2018, four people were diagnosed as infected with cholera in British Columbia due to the ingestion of herring eggs, as reported by the Vancouver Sun. Cholera first reached Canada in 1832, brought by immigrants from Britain. Epidemics occurred in 1832, 1834, 1849, 1851, 1852 and 1854. There were cases in Halifax in 1881.

Dr. Blokesch’s study entitled, Molecular insights into Vibrio cholerae’s intra-amoebal host-pathogen interactions, was published in Nature Communications.