Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, are a huge group of manmade chemicals that have been used in industry and in consumer products since the 1940s. Thanks to their incredibly strong carbon-fluorine bond, PFAS degrade quite slowly and resist heat, grease, and water making them seemingly perfect for cookware and popcorn bags, firefighting foam and textiles, and everything in between. Sounds too good to be true?

They are.

Along with the ability to keep your sandwich warm and grease-free all the way home from the deli, PFAS also brings with them a host of potential health effects, including cancer, liver damage, and decreased fertility. PFAS are everywhere which makes it challenging to study and assess both human and environmental risks. Even in remote locations where PFAS-based products are generally unheard of, traces of the chemical are being found. In the soil. In the water. And yes, even in our blood.

If we know that these chemicals exist and we also know that they are harmful, why isn’t there more information out there about them?

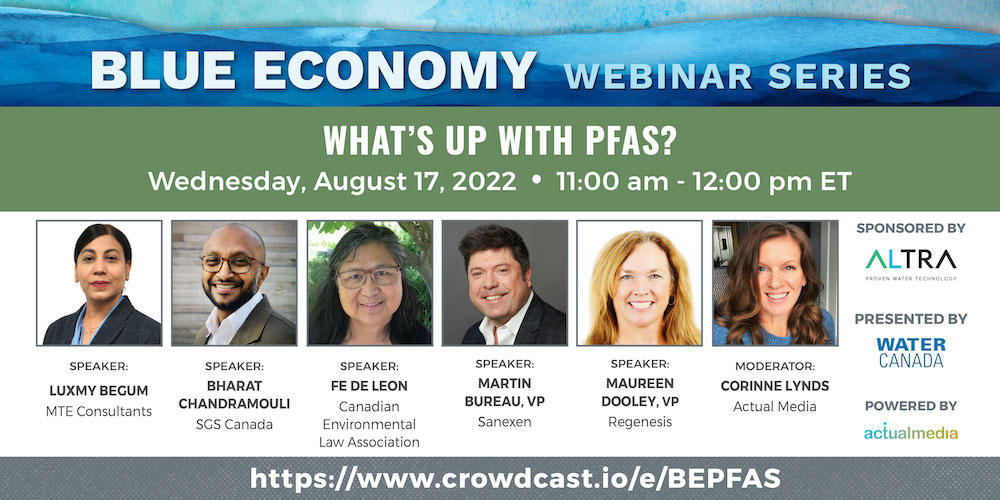

According to Bharat Chandramouli, senior scientist with SGS, PFAS’ definition itself hasn’t been settled. “The EPA has different definitions for PFAS than the OECD. And the definitions matter, because then what you regulate depends on how you define them.” Luxmy Begum, senior project manager with MTE Consultants adds, “the health effect is not yet clearly understood,” saying that we don’t fully understand the impacts or how much PFAS is safe.

This lack of fulsome definition fosters an attitude of uncertainty, which may be at the crux of inaction. But as Maureen Dooley, vice president, Industrial Sector, with REGENESIS points out, “PFAS aren’t going away, neither are the regulators. And I think it’s just a matter of time and how much.”

The possible implications of PFAS don’t end there. Fe de Leon, a researcher and paralegal at the Canadian Environmental Law Association, notes that some studies are showing that exposure to PFAS may affect women and children differently, while others point to “possible implications for the effectiveness of vaccines.” This is further complicated by the general lack of information for Canadians. This means that, “many of the communities that are affected by PFAS don’t know that they are affected.”

Why should we be concerned?

Dooley points to the siloing of roles as one of the big problems at play. She finds that “oftentimes there’s a division between the roles of the government,” which can result in a lack of information sharing and responsiveness–something she feels makes things “very reactive.”

Chandramouli agrees with Dooley’s assessment. And when it comes to where the U.S. and Canada are on the roadmap of PFAS, the difference is stark: “Canadian work is typically remediation-focused” whereas in the U.S. “it is all over the place. So much drinking water testing, so much well water testing. It’s so much response litigation, in addition to all the remediation investigation.”

He points to Canada’s lack of source information as a culprit holding them back. “The U.S. has the toxic release inventory. We don’t really have anything similar to that in Canada. So, a lot of people are in the dark.” To attempt to fight the war on PFAS, Chandramouli believes that “information and communication are key.”

Martin Bureau, vice president of Innovation with SANEXEN has experienced the effects of the lack of definitive information on PFAS in Canada firsthand. “We reached out to many Ministers of Environment in Canada and they simply don’t know about the issue at all, because it’s not on their radar.”

This doesn’t just affect larger corporations, it also affects individuals. Citing a lack of regulatory framework, De Leon calls for more accountability. “Until we start to share the data that is supposed to be accessible through open-source data on monitoring of some of these facilities, the concerns by regular Canadians who may not know to ask those questions [can’t be answered].”

What we need to do?

While conversations calling for an all-hands-on-deck approach are becoming more common, to get governmental buy-in on change, Bureau calls for a need to develop ways to address the issue that are both successful and cost effective.

Dooley also recognizes the need to get to the source of the issue, to eliminate the problem before it gets into the environment. “How do we deal with these sources, and how can we eliminate this?” Bureau agrees, looking at the process of eradicating these forever chemicals holistically: “It’s really complimentary approaches.”

Begum points out that “when the site is already contaminated, it’s a loss of huge effort. When the PFAS is already in the lake, there’s a huge effort to clean. The best approach is to stop them right at the source.” Or simply put, “separate, concentrate, and destroy.”

De Leon emphasizes the need to address “what’s possible now?” and “go up the pipe and figure out why the sources are still coming.” Bureau agrees, offering a starting point: “addressing the source point where it hurts the most, depending on what’s downstream, whether it’s a village, or a lake where people pump their water out.”

Begum sums up the next steps: Be ready. “We have to know how to treat either at the source or at the municipal level at the treatment plant. Be ready, be flexible, be able to answer questions to the public. Start preparing a technological solution. You have to answer to the public.”

This was a big topic with a power panel of passionate experts with the shared goal of eradicating this forever chemical, for, well, forever. Listen to the lively conversation in full here.

Jen Smith is the editor of Water Canada.