A new University of Victoria study suggests humans are unknowingly consuming tens of thousands of microplastic particles per year, a problem that requires further research to understand potential health impacts.

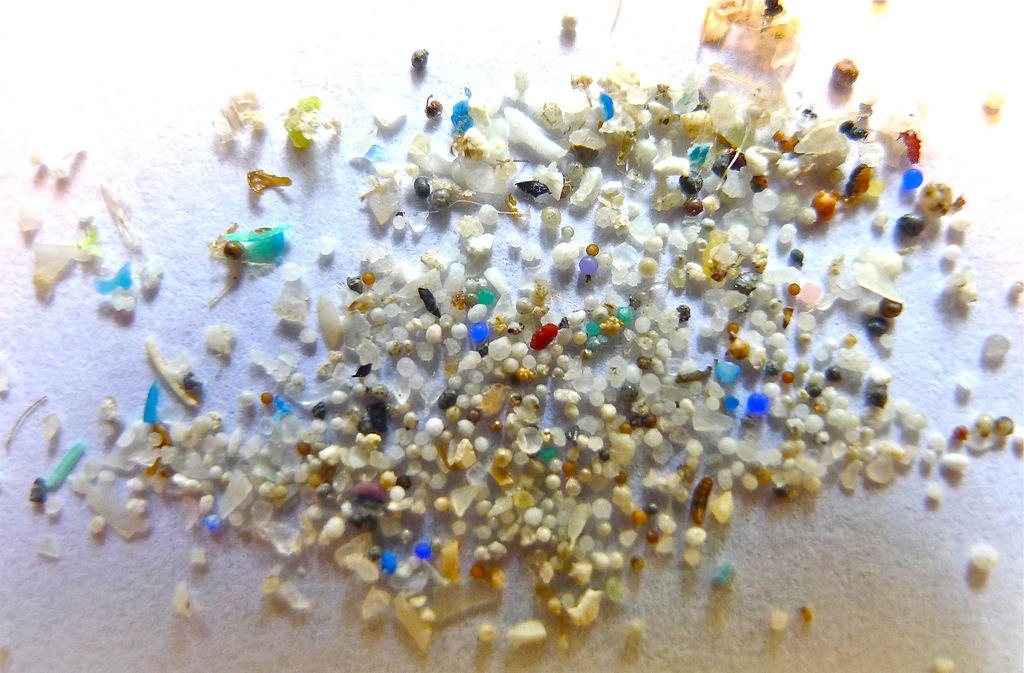

At just under five millimetres in diameter, microplastics are tiny pieces of plastic that come from the degradation of larger plastic products or the shedding of particles from water bottles, plastic packaging, and synthetic clothes. These particles can easily sneak into our bodies undetected through food or when we breathe air containing microplastics, said Kieran Cox, a marine biology PhD candidate in UVic Biologist Francis Juanes’ lab. Cox is the lead author of a research paper in the American Chemical Society’s journal Environmental Science & Technology.

“Human reliance on plastic packaging and food processing methods for major food groups, such as meats, fruits, and veggies is a growing problem. Our research suggests microplastics will continue to be found in the majority—if not all—of items intended for human consumption,” said Cox. “We need to reassess our reliance on synthetic materials and alter how we manage them to change our relationship with plastics.”

Cox and his colleagues reviewed twenty-six previous studies and analyzed the amount of microplastics in fish, shellfish, sugars, salts, alcohol, water, and air, which accounted for fifteen per cent of Americans’ caloric intake. By looking at the amounts of these foods people ate, based on their age, sex, and dietary recommendations, the team was able to estimate that a person’s average microplastic consumption is between 70,000 and 121,000 particles per year, with rates rising up to 100,000 for those who drank only bottled water.

There are limitations in available data and the health impacts are still not known, said Cox. The majority of current research has focused on seafood, but the new study indicates a significant amount of the plastic humans consume may be in the air we breathe or water we drink. More research is needed on microplastic levels in our foods—particularly major food groups like beef, poultry, dairy, and grains—in order to understand health impacts and the broader problem of plastic pollution added Cox.

The study, co-authored by scientists at UVic, Hakai Institute and Fisheries and Oceans Canada, was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Liber Ero Foundation.