It is not without a touch of irony that the very first global Action Day for Water was introduced at a UN climate summit in the Moroccan desert.

Here in the city of Marrakech, at the 22nd session of the Convention of the Parties, 113 nations came together to put the recommendations of the Paris Agreement into play. As part of the mandate of the 2016 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), this specific day is dedicated to water issues focused on solutions for water problems worldwide.

“This aligns perfectly with COP22, which is striving to be a COP of action,” said Charafat Afailal, the minister delegate in charge of Water of Morocco. “Now, we need to realize what is at stake, since water insecurity leads to increased conflicts, tension between populations, and also provokes migration that threatens overall stability.”

Benedito Braga, president of the World Water Council, echoed these sentiments: “While humanity experiences increasing demographic and socioeconomic stresses, recent episodes of extreme climate around the world bring additional complexities in finding solutions to reduce these stresses. Water is one of the most impacted resources, but water also provides solutions to these challenges.”

One of the extreme events discussed at the conference this year was Antarctica’s Larsen C Ice Shelf. Following the major collapses of Larsen A in 1995 and Larsen B in 2002, the third segment of one of the world’s largest ice shelves is on the brink of collapse, according to researchers at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS). When it goes, it will release flows of immense glaciers into the Southern Ocean, making a significant and accelerated contribution to rising sea levels worldwide.

Dr. David Vaughan, a director of science at the British Antarctic Survey, said that since Larsen C is bigger than Larsen A and B were, “the impact would be an extra significant contribution to sea level rise above the thermal expansion of the ocean and above the extra contribution from the larger part of the west Antarctica ice sheet”.

The BAS video report made by Dr. Vaughan and Dr. Paul Holland, BAS climate scientist, was presented within a new technology officially adopted by the UNFCCC as a data delivery system under its Article 6 mandate for education and outreach. Other partner programs include the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and its film production division, Television for the Environment.

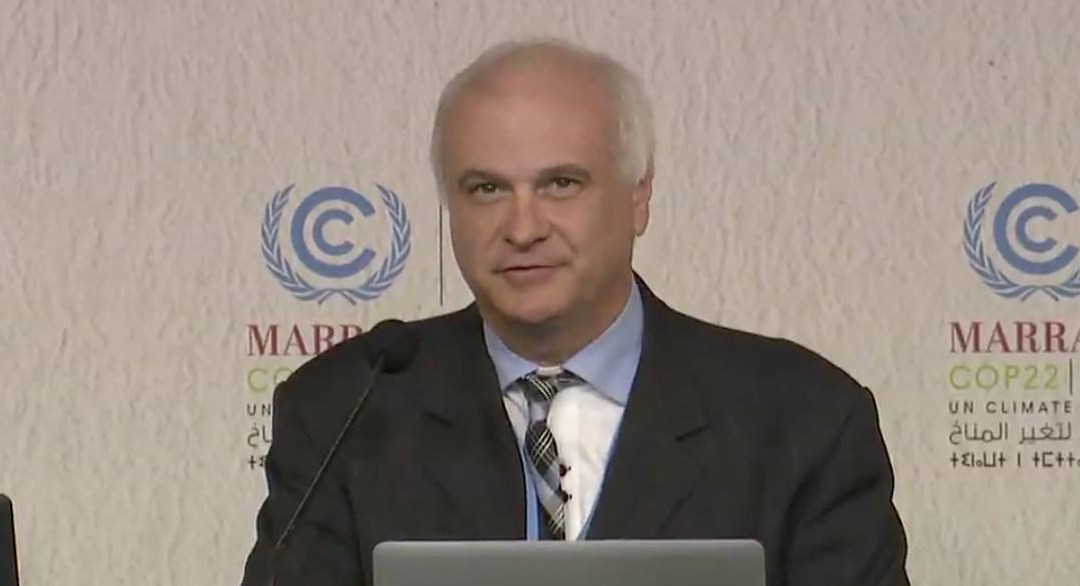

At a press conference announcing the project, Director of Communications for the UNFCCC and its spokesperson, Nick Nuttall, said he was delighted to have the opportunity to house numerous videos produced by youth of global climate research in this “easy-to-use” system. “In the future, we’ll be adding hundreds and hundreds of new videos,” he said, providing the opportunity for spatial and temporal analyses as well.

I was fortunate enough to be invited by Mr. Nuttall to attend this year’s conference and present this new technology to conference delegates and media. The project is part of my PhD research at York University in Toronto where I am exploring new digital ecologies to mobilize the documentary film as an instrument of social change. My first press conference came on the heels of Donald Trump’s successful bid for President of the United States so a lot of the media at COP22 were focused on reporting reaction to that news. However, the press who did attend were very enthusiastic over the technology that provided a “visual context” to the scientific reports in text forms previously used exclusively by conference delegates.

A video of the press conference is available on the UNFCCC website.

It should be noted here that the opportunity to work with the United Nations dates back to 1972 when UNEP was formed at the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, more commonly known as the Stockholm Conference. It was here when a specific mandate was established for UNEP to provide “an education programme designed to create the awareness which individuals should have of environmental issues” and that “(t)his programme will use traditional and contemporary mass media of communication…” Without expressly identifying film, and written in the days well before the common use of the Internet and other digital media, this mandate opened the doors for documentary film projects to participate in providing data related to environmental issues to policymakers and the public at large through UNEP.

Nearly 85 per cent of the 250 videos created for this year’s conference came from coastal communities and reference water research or water-related climate events. Further information on the Youth Climate Report map project and access to interact with the map itself, can be found at this UN link, here.

Mark Terry is a PhD Candidate at York University in Toronto.