New research has found that an approximate change of one degree Celsius in summer air temperature caused dramatic changes to Lake Hazen, the High Arctic’s largest freshwater lake.

Published at the end of March in the journal Nature, The world’s largest High Arctic lake responds rapidly to climate warming, features work from a number of Canadian scientists with international partners.

“I think there was an assumption that because [Lake Hazen] was bigger and probably had a more complex ecological system it would probably be a bit more robust in the face of rapid change than small systems would be. But that’s not the way it turned out,” said Martin Sharp, Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, and co-author of the research told Radio Canada International in a recent interview.

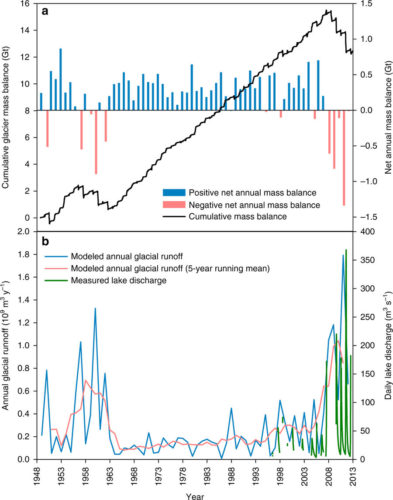

Dramatic changes include the water residence within Lake Hazen, the research finding that “the large input of glacier meltwaters into Lake Hazen has reduced the residence time of water in the lake from its historical average of 89 years to only 25 years.” The decrease in residence time is precipitated by meltwater from the glaciers within Lake Hazen’s catchment. “Modeled mean rates of annual glacier runoff reached 660 kg m−2 or 1.8 km3 y−1 over the entire Lake Hazen catchment in 2011 (Fig. 4).”

“There was a big change in the duration of lake ice cover on the lake, so that open water became kind of the norm for much larger parts of the summer than had been the case historically,” Sharp told Radio Canada. “So, that would have affected the light regime in the lake, and there would be consequences for the organisms that live in the lake.” The ecological impacts have been felt by Lake Hazen in the form of shifts from substantial shoreline benthic species populations to open-water planktonic species having greater abundance.

As well, the lake’s population of Arctic Char—the only fish species in the lake—have undergone a decline in physiological condition. Sharp noted that the impact on Arctic Char is most likely due to the amount of fine grain sediment coming from increased glacial drainage into the lake. “That sediment would increase the turbidity of the water column, because it settles out so slowly, and because char basically hunt for food in the water column, that sediment would reduce their visibility and, maybe, make it harder for them to find prey.”

The researchers concluded that “collectively, these changes place Lake Hazen in a biogeochemical, limnological and ecological regime unprecedented within the past 300 years.”

The research can found on nature.com, and the interview with Sharp can be found on Radio Canada International’s website.