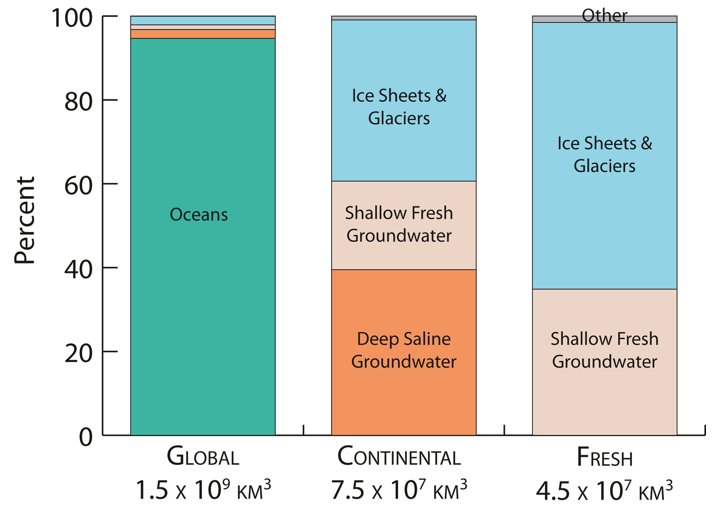

More water lies within the Earth’s continental crust than previously thought, according to new estimates published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. The estimates indicate that the planet’s land mass groundwater is the largest store of water in any form, larger than ice sheets.

These are some of the main findings of a study by lead author Dr. Grant Ferguson (PhD) from the University of Saskatchewan (USask) and his co-authors, an international and interdisciplinary group of scientists studying the earth’s subsurface biosphere. The newly published estimates are critical to their work.

“We know that there’s life,” Ferguson explained. “There’s been cell counts in these waters down to several kilometres. A lot of those estimates are based on how much water is available, how much pore space for these microbes to live in.”

The examination of deep groundwater reservoirs has implications for a wide array of challenges: the search for life on Mars, better understanding the origins of life on Earth—even underground nuclear waste storage and extraction of lithium from these waters for such uses as electric batteries.

The paper builds on earlier work published in 2018 that focused in particular on water held in crystalline rock, the type that makes up the Precambrian shield and accounts for about 72 per cent of the continental crust. Ferguson added sedimentary rock to the calculation, and also looked at how porosity in rock may change at various depths thus affecting water volumes. Rocks hold water in holes or pores, much like a sponge.

The finding that crustal groundwater is a larger reservoir than ice sheets “has important implications in terms of how we think water has been moving around the planet for quite a long time,” Ferguson said. It’s known that some of these waters at depths of several kilometres can be millions of years old or, in some cases, more that a billion or more years old “so it rewrites how we think about how water cycles on our planet.”

A copy of the article is available here.