WATERLOO, Ont. – Sheri Longboat (MA ’96, PhD ’13) has always felt a deep personal connection to water. Since her earliest years growing up beside Lake Ontario in Hamilton, Ont., her “reverence and respect” for water has driven her to help protect it.

Upon graduating from Wilfrid Laurier University with her master’s degree in 1996, Longboat’s first job was mapping the Haldimand Tract land claim with Six Nations of the Grand River, of which she is a member. She continued to work with Indigenous communities on sustainability and capacity building, noting the “pressing inequality” she observed inspired her to return to Laurier and complete her PhD in 2013. Longboat investigated the lack of water security in many First Nations across Canada, an issue that persists to this day.

“There should be no reason to not have safe drinking water in every First Nation community,” she says.

Longboat recently returned to Laurier again, this time as an associate professor of Geography and Environmental Studies. Water security and management remain the focus of her research, prioritizing practical solutions to First Nations-identified needs in Indigenous communities.

“As a Haudenosaunee, Six Nations woman, I feel that I have a responsibility, now that I’m in the academy, to make place and space for others and dedicate my time to elevating Indigenous voices and supporting communities,” says Longboat.

As World Water Day approaches, Longboat shares how she is confronting the water “crisis” in First Nation communities through her collaborative research.

Much of your research is addressing what you refer to as a national water “crisis.” How did this crisis arise?

It’s a legacy of persistent colonialism. Many Indigenous nations are on very poor land and the treaty process enabled those reserves. Furthermore, Canada has a two-tiered system in that all Canadians who don’t live on a reserve have robust water governance and management systems protecting them, but if you live on a reserve, your home falls under federal jurisdiction and you’re not guaranteed those same rights. This crisis is a result of political inaction because our government hasn’t made it a priority to fix it. The issue has been othered – out of sight, out of mind.

In your experience, how are communities affected by a lack of safe drinking water?

Part of my PhD research was listening to these stories and what I found to be unique was the impact unsafe water has on people’s relationships with water. This is a sacred relationship for Indigenous peoples, and yet many are afraid of the water, both coming out of the tap and from natural water bodies. They often won’t swim in it. They worry about accessing it for ceremony. At its core, it’s the spiritual relationship with all of creation that is impacted.

Then there’s the human health and safety risk. I’ve heard of northern communities whose residents are struggling with skin problems and physical manifestations of the lack of safe potable water. We see communities facing decades of drinking water advisories and relying on bottled water, at great expense. From a community growth perspective, many First Nations have finite land bases and limited infrastructure, so they can’t build houses or support economic development. It becomes cyclical where the lack of water is limiting the ability to develop.

Yet many communities are resilient and are still growing, finding their own source revenue, building partnerships, working with municipalities, asserting their rights, filing legal cases. There is research showing that the contributions of Indigenous peoples to the Canadian economy are immense if we can just ensure the equity and justice they need to excel.

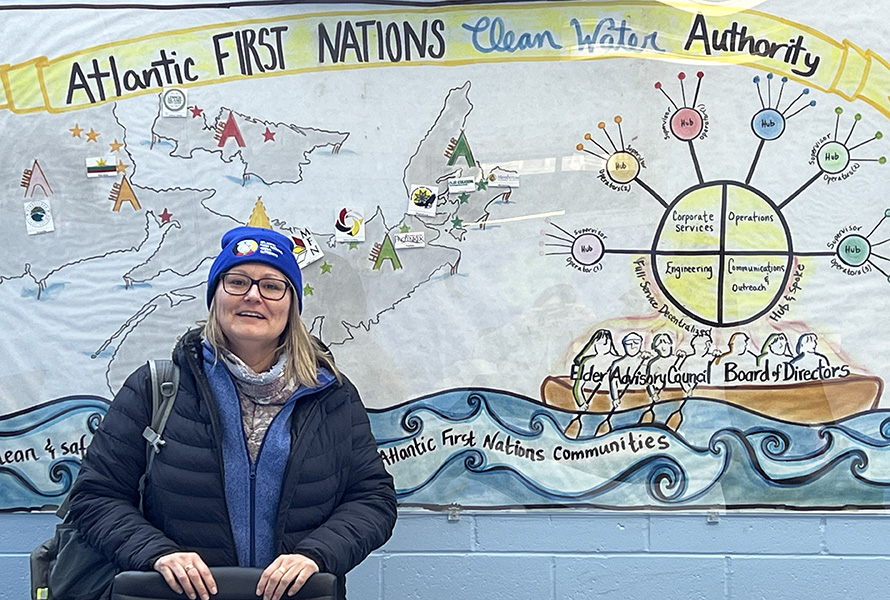

Longboat (right) working with colleagues Megan Fuller (left) and Toni Stanhope (centre) at Dalhousie University’s Centre for Water Resources Studies.

Why is self-governance so important for addressing this issue?

I have heard quite often from First Nations members that they want to have control over their water systems, largely because of fear – a justified fear of environmental colonialism. For one research project, we looked at the feasibility of water sharing with municipalities. This may be a viable short-term solution for some. However, I remember a community member saying, “Even if we get safe water, I don’t know if our people will feel safe.”

Indigenous peoples need to be involved in the governance of the water and the lands within their traditional territories. In addition to drinking water, there are activities happening upstream that affect natural water bodies, such as mining and other development, yet the communities are not part of the decision-making. They generally have no say, and they rarely reap any of the benefits of the development that happens within their treaty territories.

We need to start making co-governance arrangements the norm, going back to the original treaties and the Two Row Wampum principle of peaceful coexistence. We are meant to take care of the land and water together. Then we can begin to foster sustainability that will benefit all people, not just Indigenous peoples, and fulfil responsibilities for future generations.

What are some of the practical solutions you’ve co-created with First Nation communities?

We have helped communities gain certainty over the quality of their water through sampling and testing, as well as to explore the benefits and risks of municipal-type water agreements. We worked with another community to develop a nation-informed water security planning framework. They were interested in how to elevate and integrate water within their decision-making processes and include water sustainability in their capital and community planning, much like would be done in other jurisdictions. These communities remain greatly challenged, though, because the Indian Act limits their governance and powers, and federal control through policy and limited funding prevents effective water management planning and development. The bottom line is that until they receive adequate funding to fix infrastructure, upgrade facilities, hire more operators – those core elements – a lot of the planning work can’t be implemented.

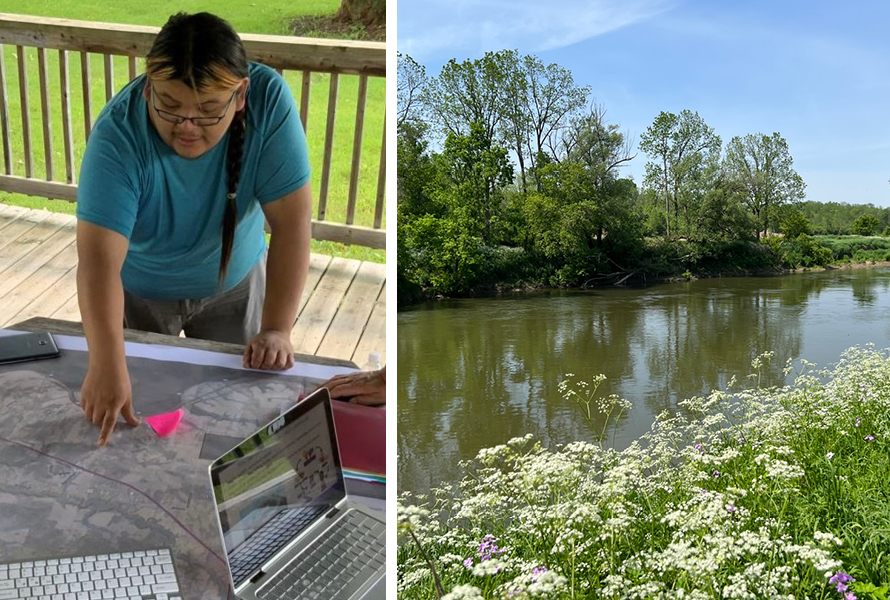

Left: Longboat’s collaborator, Brandon Doxtator from Oneida Nation of the Thames. Right: Thames River.

What are some of your current water-related research projects?

I have projects on the go at local, provincial and national levels. Locally, we are working with the Oneida Nation of the Thames to develop a risk assessment tool from a Haudenosaunee perspective. We’ve done soil and water sampling with them in the past and this decision-making tool will incorporate their views, values and knowledge systems to determine how they wish to measure risks to their community.

With funding from the Ontario Agri-Food Innovation Alliance, we are co-developing materials and updating best management practices for private water wells in rural communities. The current guidelines are more than 20 years old, so we’re engaging community-based organizations and experts across Ontario to make them more reflective of current rural communities. Most importantly, we’ll be developing awareness materials that are accessible to well owners.

Nationally, we’ve been funded by Indigenous Services Canada to develop an expert report on First Nations decentralized water and wastewater systems, which are band-managed, small-scale systems. To date, much of the emphasis has been on the larger centralized systems. Collaborating with the Centre for Water Resources Studies at Dalhousie University, we have reached out to every First Nation across Canada to seek their “expert” input. In the coming months, we are conducting virtual meetings and planning to visit a few First Nations in every province and territory. We seek to understand the risks, challenges and experiences around decentralized systems and their management. Then we will summarize what we’ve heard, along with a rich literature review, to provide recommendations to Indigenous Services Canada.

How does it feel to be back at Laurier, continuing research you began here as a PhD student more than a decade ago?

It’s wonderful. I’m proud to be back. Coming back to Laurier is also coming home to Haudenosaunee territory within the Haldimand Tract, which is important to me. So is the commitment that Laurier has made to decolonization and Indigenization, with respect to supporting Indigenous peoples and learners on our campuses. There is always more to be done, but I’ve always thought Laurier is a leader in that regard. One of my goals is to bring more Indigenous students to Laurier and I think we’ve made a really good space for them to flourish.