Are Toronto’s streams sick? Yes, many of them are. They are suffering from an “illness” known as urban stream syndrome (USS), which results from changes associated with urban development. The hardening of surfaces, such as roads and roofs, creates a landscape that makes it difficult to absorb rainfall. In areas without proper stormwater management, the volume of stormwater is high and runoff collects sediment, nutrients, and contaminants as it travels across hard surfaces, causing streams to function more like sewers. Symptoms include changes in the aquatic community, hydrology, and water chemistry.

The Greater Toronto Area has approximately 5.5 million people. This has put pressure on its approximately 3,654 kilometres of streams and watercourses. The Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA), one of 36 conservation authorities in the province, has been tasked with protecting and managing water and other natural resources in partnership with government, landowners, and other agencies.

The Greater Toronto Area has approximately 5.5 million people. This has put pressure on its approximately 3,654 kilometres of streams and watercourses. The Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA), one of 36 conservation authorities in the province, has been tasked with protecting and managing water and other natural resources in partnership with government, landowners, and other agencies.

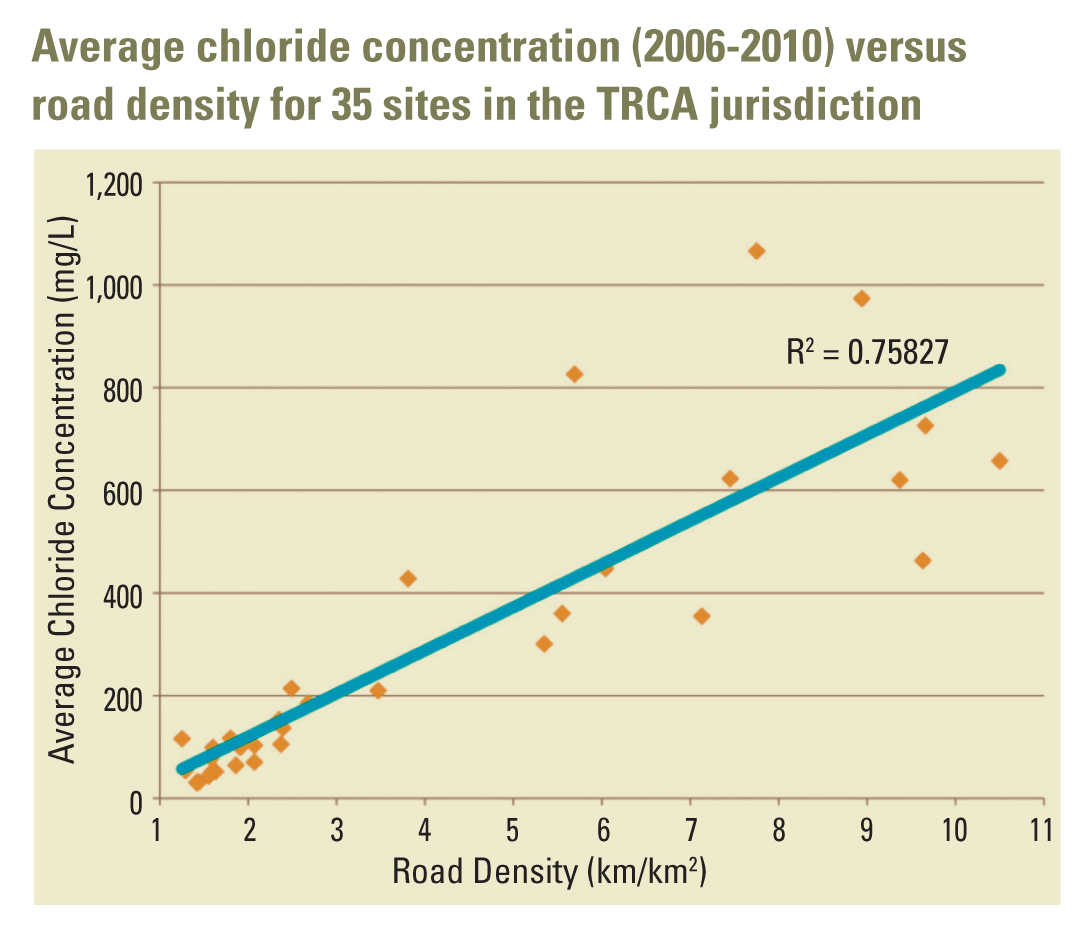

TRCA operates a long-term, large-scale Regional Watershed Monitoring Program (RWMP), which tracks aquatic habitat and species, surface water quality, stream flow, precipitation, groundwater quality and quantity, and terrestrial natural heritage in nine watersheds across 3,467 square kilometres. Data from the RWMP was recently used to show that streams in the Toronto region have USS. Road density (used as a surrogate of urbanization) was shown to be related to the USS symptoms. Both fish and benthic-macroinvertebrate (aquatic “bugs” that inhabit stream bottoms) communities were negatively related to road density. Higher road density was also linked to decreases in aquatic ecosystem health (biotic diversity), higher stream water temperature and discharge, lower amounts of forest, and higher levels of contaminants.

In fact, concentrations of nutrients, metals, and bacteria were all higher in catchments with higher road density; several contaminants, including chloride, copper, E. coli, sodium, and zinc, had very strong relationships with road density, suggesting they are more abundant in urban areas and that impervious cover may serve to concentrate and convey these variables quickly to local waterways. According to the Environmental Monitoring and Assessment paper Are Toronto’s Streams Sick?, the degree of sickness was most severe in the lower portions of our watersheds where road density tends to be the highest. But the deterioration has occurred even in areas where conventional stormwater management planning and design has been implemented.

What’s the cure?

Can Toronto’s streams be cured? Stream degradation in urban areas has numerous causes, but hydrological changes play a big role in the function of our streams and the shaping of their aquatic communities. Stormwater causes streams and rivers to be more vulnerable to flooding, erosion, and pollution. Low-impact development (LID) has been identified as a management approach with the potential to help reduce the impacts of stormwater. Traditional stormwater management focuses on capturing and piping stormwater while LID seeks to mimic the water-absorbing capabilities of a natural undeveloped site. When rain falls in nature, it slowly infiltrates through soil and vegetation, which act as a natural filter. LID tries to alleviate the impacts of stormwater by managing runoff as close to its source as possible, therefore reducing the amount (and improving the quality) of stormwater that reaches our waterways. Examples of LID techniques include site naturalization, infiltration/soakaway pits, rainwater harvesting, permeable pavement, and green roofs. WC

Angela Wallace is a biomonitoring analyst at Toronto and Region Conservation. This article appears in Water Canada’s November/December 2013 issue.

Nice to see a focus on urban watershed anti-degradation. Now if only we had a national Clean Water Act, regulations and LID mandatory infrastructure expenditure focus, well we’d be up to the present. As it is, Canada exists in some 1960s Tim warp where deregulation makes even the hoary old Fisheries Act seem progressive.

Not to be picky, but the #1 focus of urban watershed LID is pollution prevention. In a city undergoing so much development , it is appalling there is no enforcement of the sewer use by-law on as simple an issue as construction site sediment control.

Just a thought.