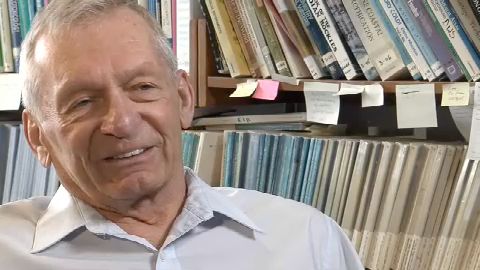

As the Canadian Society for Ecology and Evolution’s biannual award winner, University of Alberta’s Dr. David Schindler was invited to write a review for the Royal Society B: Biological Scienceson a topic of his choice—he chose phosphorus control. When Water Canada spoke with him on Friday, he argued that whole lake manipulations are superior to lab-based experiments in determining the role of phosphorus and nitrogen in the problem of eutrophication. We asked him to tell us more.

Water Canada: In your opinion, what are some of the drawbacks of lab-based experiments versus whole-lake manipulations?

David Schindler: Experimental Lakes Area [a federal field research station in northwestern Ontario that consists of 58 pristine lakes] studies show that several mechanisms are not part of short-term bioassay tests. There are a lot of large-scale processes in lakes that take years to respond. For instance, if you remove a predatory fish species from the lake, all organisms that the predator normally eats will increase [in population], but it takes years to reach equilibrium. If you reintroduce the predator, initially it will have a lot of the food that it needs, but it takes the lake several years to return to harmony. An experiment that lasts two hours or at longest a month doesn’t catch [that aspect], and there are a number of things we miss when we rely on short-term experiments.

Recently, the federal government announced that it will discontinue funding for the ELA, and you’ve publicly advocated on its behalf. What can you tell us about this decision?

If the ELA is gone, we will never have a similar area again. Since [the time when the lakes were set aside for research purposes], the logging industry has mechanized. If the area was closed [to research] now, it would be logged entirely within a few years. We would lose the pristine quality to competing interests. The ELA’s 44 years of databases have been very valuable in showing trends caused by climate warming, nutrient and calcium inputs, et cetera. This is not the sort of thing that can be remedied by setting up another program in [somewhere else] Canada.

If the Harper government does indeed go through with its decision to make the cut, is there an alternative way to continue the ELA’s research?

I’d like to see funding from industrial sources or a university consortium. The only way for a consortium to work would be to open participation to American universities and have the consortium report to a panel of senior scientists.

So the ELA should not remain a responsibility of the federal government?

I’d like to see the ELA taken out of government. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans has been a terrible department to manage [this] project. The people in charge don’t understand the science; they only look at the department mandate. They say, “If you’re not studying cod or salmon, it’s not on our priority list” and that the fresh waters are a provincial responsibility. They say they’re eliminating duplication, but if you look at what’s going on, we have a situation where neither provinces nor federal governments are looking after fresh water in this country. If the politicians in charge don’t like the data, they simply direct their scientists not to release the information. That’s not the way a democracy should work. Something has to be done.