Twenty years ago, in May 2000, a municipal well in the Town of Walkerton, Ontario became contaminated with deadly bacteria. Seven people including a child died due to the contamination, and thousands were left with severe long-term illnesses. A waterfall memorial there is dedicated to the victims of this drinking water tragedy, and reminds us about the necessity of proper water management.

Multi-barrier approach to drinking water protection

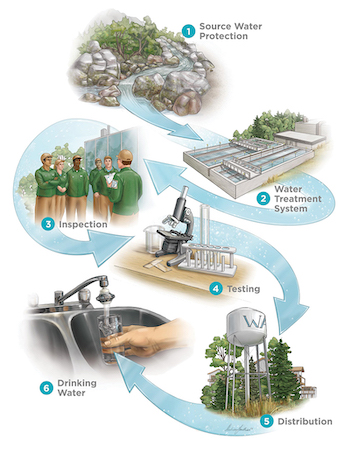

Since the Walkerton tragedy, vast improvements have been made in drinking water safety in Ontario due to recommendations stemming from a public inquiry led by Justice O’Conner in 2001. Those recommendations are the building blocks of Ontario’s multi-barrier framework that includes the Safe Drinking Water Act (2002), the Clean Water Act (2006), and other laws.

Conservation Ontario, the network of Ontario’s 36 watershed-based conservation authorities, provided recommendations to the public inquiry including the need for watershed management to protect our drinking water sources.

Since water quality test reporting began in 2004, more than 99.9 per cent of the tests for over 522,000 municipal drinking water systems continue to meet Ontario’s water quality standards. Municipally-treated drinking water is delivered safely to over 80 per cent of Ontarians who can trust the tap. Water treatment is part of the multi-barrier approach, and it follows the first step of protecting the source water quality and supply.

The Great Lakes, inland lakes, rivers, and groundwater aquifers are our sources of drinking water, and we need to protect them from contamination and depletion.

Achievements in protecting drinking water sources

In Ontario, the Clean Water Act mandates the protection of sources of municipal residential drinking water systems, through local source protection plans. Certain other types of drinking water systems can be included as well.

The Clean Water Act establishes the framework for local, multi-stakeholder decision making on a watershed basis, in step with Justice O’Conner’s recommendations. There are 19 source protection committees representing municipal, economic, public, and Indigenous interests.

They carry out their responsibilities supported by the watershed expertise of source protection authorities, who are comprised of Ontario’s conservation authorities, the Severn Sound Environmental Association, and the Municipality of Northern

Bruce Peninsula.

The committees led the development of 38 local source protection plans. These plans include science-based assessment reports that provide a strong foundation for policies.

The assessment reports include delineations of drinking water protection zones around municipal wellheads, surface water intakes, highly vulnerable aquifers, and significant groundwater recharge areas. These zones are based on local science and follow methodologies established by the provincial government.

The source protection plans also contain policies that manage certain activities within drinking water protection zones for:

- Over 900 groundwater wells.

- Over 70 Great Lakes intakes.

- Over 60 inland lake intakes.

- 13 Lake St. Clair and St. Lawrence River intakes.

Most source protection plan policy implementation began by 2015, with two-thirds of the implementation by municipalities, close to one-third by provincial ministries, and the rest by conservation authorities and others.

Policy tools used include land use planning, risk management plans, permits, and educational programs. Source protection authorities indicate that support from landowners, who implement management measures within protection zones, has been a strong element of success of the program. Other successes include:

- Over 1,000 risk management plans have been established.

- Over 5,000 septic systems have been inspected.

- Over 900 road signs have been installed to identify drinking water protection zones.

The Clean Water Act also supports a continuous cycle of improvement through annual progress reporting and source protection plan updates. Source protection authorities collect information from policy implementers every year to develop progress reports on policy implementation. The plan policies are based on science and approaches that are updated as needed to reflect changing activities on the landscape, growth and development pressures, and other factors.

Finding solutions with watershed management

As we look back at the twenty years since the Walkerton water tragedy and recognize all that has been accomplished, we must also reflect on the lessons learned, plan for challenges ahead, and continue our efforts to protect our sources of drinking water.

A healthy watershed is key to a healthy community and a thriving economy. Conservation authorities and others have long supported elements of source water protection through their local watershed management programs that help to prevent and manage many source-water issues. The multi-stakeholder, collaborative and watershed-based approach in Ontario will continue to help face both ongoing and new challenges in source water protection.

We are living in a markedly changing climate and face exacerbated conditions including warmer temperatures, floods, and droughts. In parts of Ontario, flood events severely impact residents with private water supplies such as wells due to the high risk of contamination. As well, many First Nations communities are challenged with long-term drinking water advisories of boil water, do not consume, or do not use.

Emerging contaminants like PFAS (per and polyfluorinated alkyl substances, commonly used in firefighting foam) are a public health concern health. At the same time, we face new unknowns like microplastics for which human health impacts are not fully studied yet.

Watershed-based source protection planning balances economic, social, and environmental needs for healthy and prosperous living. For example, water budget studies show where adequate water supplies exist to support new or growing populations.

Watershed monitoring allows for the early detection of climate change impacts, including water quality and supply problems. Watershed-based policies help protect both existing and future water supplies, spanning political boundaries. These are crucial components of watershed management, without which we may become vulnerable to water contamination and lack of adequate water supply.

Twenty years after the Walkerton water tragedy, it is more apparent than ever that watershed management is necessary across Ontario to protect our precious sources of drinking water.

This article was written by Kim Gavine and Chitra Gowda for the July/August 2020 issue of Water Canada. Kim Gavine is the general manager of Conservation Ontario. At the time the article was published, Chitra was the source water protection lead at Conservation Ontario. As of October 2020, she is currently the senior manager of watershed planning and source protection at Conservation Halton.