In 2010, Suncor Energy’s Edmonton refinery drew 50 per cent of its water from the City’s Gold Bar Wastewater Treatment Plant, significantly reducing the amount of fresh water withdrawn from the North Saskatchewan River. When the arrangement was first made a few years prior, the case was largely an anomaly. But, as government puts more restrictions on industrial water use, these types of collaborations are now becoming more commonplace.

Working primarily with energy and industry clients, Jan Dell, a vice president at CH2M HILL, says finding sustainable water sources for operations is often one of the biggest challenges. “We often get to the point, especially in water-stressed regions, where industry isn’t allowed to use fresh water, and they’re looking for alternatives,” Dell says. “Municipal effluent is a really great source. It’s there, it’s waiting, it’s not being used.”

Dell says the trouble is a lack of communication. “We have to get industry, agriculture, and municipalities outside of their own fences,” she says. “Like-minded people need to meet each other, but we need new approaches.”

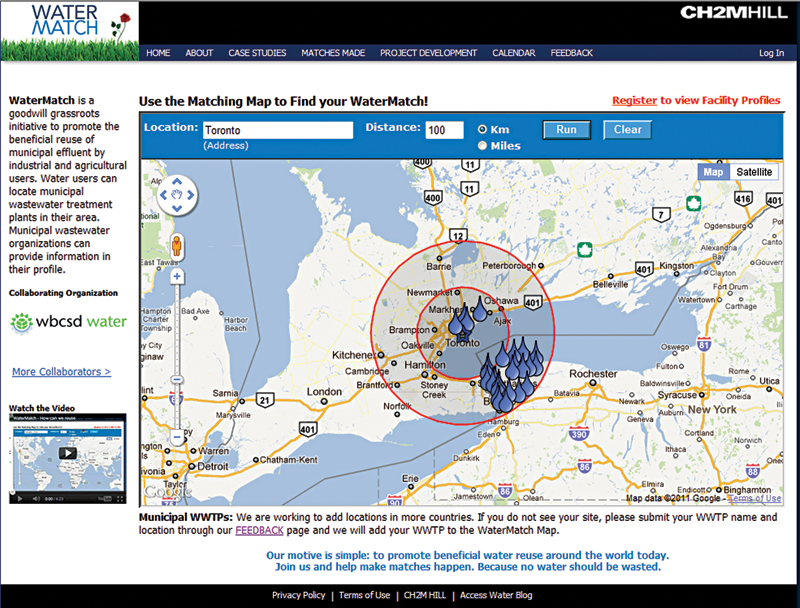

CH2M HILL is giving it a try. At this year’s WEFTEC conference in Los Angeles, the company launched WaterMatch, a public domain “virtual meeting space” that uses social networking and geospatial mapping to connect water generators with water users.

How does it work? Once registered, water users use a map to find wastewater treatment plants close to their current and potential future operations. Then, they use the social networking function—Dell likens it to Facebook or, more appropriately, match.com—to connect with the utilities operating those plants. If the plant is available to provide effluent, the two are encouraged to connect offline and explore the possibilities. For every “match,” CH2M HILL has pledged to donate $25 to Water for People.

WaterMatch has the support of more than 200 global businesses through the World Business Council for Sustainable Development and IPIECA (the global organization of oil and gas companies). “We’re in great shape,” says Dell.

Currently, says Dell, the WaterMatch map also contains about 20,000 treatment plants from around the world, but Canada has been a challenge because no public list of wastewater plants is available. Dell says that once the word gets out, she hopes municipalities will check to see if they’re plotted. If they’re not, they’re encouraged to submit their information.

So far, the site hasn’t garnered any matches, but it’s just the beginning and Dell is hopeful. “We’re all working so hard on solving water issues,” she says. “Water reuse is a win-win for municipalities and industry. When that happens, there are lots of benefits to the ecosystem and otherwise. We’re trying this approach because we think no water should be wasted.” WC

I am suprised to read a statement like “It’s there, it’s waiting, it’s not being used.” as if wastewater treatment plant effluent was kept on the property without any discharge to a river to be used by an other Community downstream. If some or all of it is discharged to the river after being used by the industry, will its quality be the same or better than the quality of a municipal wastewater treatment plant effluent?