One of the most tangible and costly effects of global climate change is major, often catastrophic, floods. In Canada, where upwards of seven million people live in either a coastal or riverine flood plain, it’s clear that the impact of climate change-driven massive precipitation events, spring freshets, and rising lake levels have been taking an increasingly heavy toll on Canadian communities in recent years.

At the same time, the recorded instances of urban flood events in Canada have been steadily mounting over the past decade, with the costs of repairing the damage caused to residential properties—particularly the flooding of home basements—cumulatively registering in the hundreds of billions of dollars during this period.

According to a study published in February 2022 by the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation at the University of Waterloo, flooding—and more precisely residential basement flooding caused by extreme weather events—accounted for more than half the nearly $2 billion in average annual property damage claims in Canada between 2009 and 2021. That figure is at least a four-fold increase over the $250-$450-milllion annual average of insurable residential losses recorded between 1983 and 2008.

While there is some debate as to how dramatic an increase in overall mean rainfall there has actually been across the country over the last several decades, there have unquestionably been a number of intense, damaging rain events in Canada over the past 10 to 20 years.

Failing infrastructure

However, when it comes to urban flooding events, extreme weather is often not the only culprit. In fact, the cost of property damage caused by aging, failing urban stormwater collection and sanitary sewer systems that are unable to handle historically normal capacity may be even higher than that caused by so-called atmospheric rain bombs, such as the one the city of Toronto experienced in July 2013.

Of course, when cities like Toronto have to manage sewer and drainage infrastructure that in some cases is approaching 100 years in age and is characterized by combined, sanitary and stormwater drainage pipes, it’s not surprising that large parts of the systems do not come close to meeting today’s design standards. Even where portions of sewer and drainage systems may have been upgraded to more modern standards in the 1960s, ‘70s, or ‘80s, they often still come up short of what is needed to adequately handle increasing stormwater runoff and wastewater flows.

To be clear, the problem of climate-driven urban flooding has been exacerbated by a combination of aging urban sewer infrastructure and flood mitigation design practices that have not lived up to their promise, coupled with growth and intensification in already dense urban areas.

Right tools for the job

For Canadian municipalities, being able to accurately assess and ultimately mitigate the risk of flooding within their local area, whether it be from overland stormwater flow or sewer backup, requires having the right tools to do the job.

Although stormwater drainage systems are technically not connected to sanitary sewage systems, there is, under the right conditions, the opportunity for these separate systems to impact one another during significant events, even more so when taking into account older combined sewer systems. This is further complicated when considering the potential influence of receiving waters, such as lakes, creeks, and rivers. Consequently, a comprehensive approach to evaluating flood risk should include all types of systems and drainage conditions.

When an urban basement floods, it is often a sanitary sewage backup driven by excess inflow and infiltration. Equally, it can be a result of storm sewer backup driven by an overloaded storm sewer or through overland flow entering a window well or other vulnerable locations around a building. The flooding situation can be further complicated by the possibility that riverine flood water has backed up into the storm system or flowed overland into neighbourhoods.

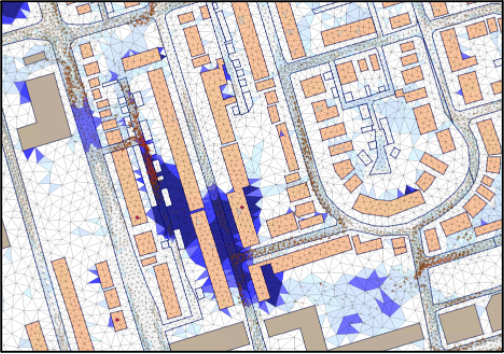

Any municipality trying to understand the risk of flooding in their community in order to develop effective mitigation and protection measures needs to consider all drainage systems and conditions to identify how stormwater runoff flows overland, is intercepted by the storm drainage system, and how it influences wastewater systems. This is now possible with the availability of accurate elevation information (LiDAR) and 2D flood modelling tools to assess and analyze how overland flow systems work and where storm runoff goes, and what systems it may influence.

2D flood modelling

Today, a number of sophisticated 2D flood modelling software solutions are available to help municipal engineers better understand and mitigate the flood risks in their area, whether it be in an urban, riverine, or coastal setting.

One of the key benefits of 2D technology is that it enables a more comprehensive assessment of the potential flood risk to important infrastructure that wouldn’t typically be captured or seen in an older dual-drainage or 1D flood risk study.

The volume and type of data needed to prepare a 2D model are not that dissimilar to a more traditional 1D model. Both require good infrastructure information, typically contained within municipal GIS systems. The critical component of 2D modelling is surface elevation data with a resolution that is on the order of +/- 20cm vertical accuracy or better. This information is critical to defining the surface where features, such as roads or other drainage features or surfaces are clearly defined. This level of precision can be used by a 2D flood modeller for extremely accurate predictive and remedial flood planning.

Simpler tools may be effective

Unfortunately, as the prioritization of flood mitigation and protection planning has become more prevalent in towns and cities across Canada, the use of complex and expensive proprietary 2D flood models is becoming more common and an almost automatic de facto standard approach, when simpler, faster, cheaper tools may be a more effective option in many cases.

Make no mistake, 2D flood modelling offers many compelling benefits, but it isn’t necessarily best suited for all flood planning exercises, particularly when assessing smaller areas with simpler systems.

For instance, urban flood risk can often be mitigated by taking steps to reduce the inflow of water to the local sewer system and increasing the flow capacity and water storage capability within the system. There are obviously many factors that need to be considered and analyzed to arrive at the best mitigation solution, but the need for 2D modelling is not always there.

Collaboration is key

In fact, the best solution for many municipal engineers looking to address an urban flooding problem may not be about technology at all. The key is often to talk directly to other municipalities that are using a variety of different planning and modelling tools and discuss what has worked and what hasn’t under a wide variety of scenarios. In particular, for smaller municipalities with limited resources and in-house technical capabilities, the willingness to collaborate with other municipalities or agencies is critical.

While many municipal jurisdictions across Canada are wisely earmarking funds and actively upgrading their stormwater collection and sewage infrastructure to help abate the risk of urban flooding, the potential for widespread, damaging floods remains extremely high.

Thus, whether dealing with stormwater or wastewater systems, municipalities need to continuously and objectively evaluate the flood risk scenario confronting them and make informed decisions about which flood prevention and mitigation planning strategies and tools will work best for their specific needs. One size fits all approaches should always be avoided.

Philip Gray, P.Eng., P.E.is an Associate Director, Infrastructure Planning for IBI Group specializing in master planning and wet weather issues through the development and application of hydrologic/hydraulic models to evaluate complex watershed and municipal systems through many projects across Canada and in the United States.