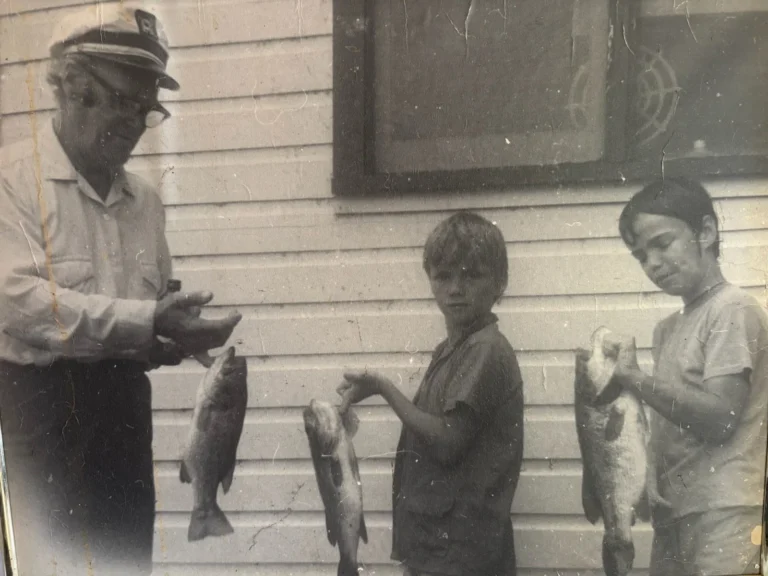

The Asubpeeschoseewagong Netum Anishinabek (Grassy Narrows) First Nation has been living with the effects of mercury poisoning for over a generation. While liability has not been established, it is known that between 1962 and 1970, the Reed Paper’s chemical plant in Dryden dumped 10 tonnes of mercury into the Wabigoon-English River.

When high levels of mercury were discovered in the fish in 1970, the Ontario government closed the local commercial, tourism, and subsistence fisheries. This removed a primary income source for the Grassy Narrows people and an important part of their diet and their culture. But nothing was done to remedy the contamination.

Over the years, environmentalists, scientists, federal and provincial governments, and the First Nation community itself, have attracted attention for their actions, inactions, and calls for action to address contaminated areas. In 1984, an expert panel of federal and provincial scientists put forth a remediation plan. But the Ontario government did not act. Recently, the Grassy Narrows First Nation recently commissioned a team of mercury contamination experts to revisit the situation and recommend the best solutions to decontaminate the water. They recommended a thorough investigation to find the source of what appears to be ongoing, low-level contamination and remediation of the river system using Enhanced Natural Recovery (ENR) and nitrate injection techniques.

credit: Schledewitz redlineagency.com

Ongoing source

Dr. John Rudd is a former federal researcher that conducted the original three-year study of the Wabugoon-English river in the early 1980s. Dr. Rudd and his team have and continue to assert that the river can and should be cleaned up. Ultimately, he led the latest investigation for the Grassy Narrows community, and upon thorough inquiry as to the source of what appears to be ongoing, low-level contamination, recommended remediation of the river system using Enhanced Natural Recovery (ENR) and nitrate injection techniques.

In their findings, released May of 2016, Rudd and his colleagues reported that although, initially, the river seemed to be cleaning itself, recovery has stalled. They believe the upper lakes, Clay Lake and Ball Lake, could still be receiving mercury input from upstream [where the former Reed Plant sits], either from mercury trapped in sediments and eroded during times of high flow, or from leakage occurring at the site of the old plant.

“It’s very common that former chlor-alkali plants continue to leak mercury at a much reduced, but still significant rate after they’ve been closed down. This can go on for decades,” explained Rudd. In addition to his experience at the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and as chief scientist of the Experimental Lakes Area research station, Rudd has worked on two major industrial mercury remediation projects in the United States.

Earlier this year, the environmental organization Earthroots took soil samples in an area pointed out by a former Dryden mill worker and found very high concentrations of mercury. Rudd said that while this dump could be the source, “there is often a lot of mercury under the concrete floors of buildings where chlor-alkali cells were formerly located.” Either way, he said, a complete investigation of the site is needed, so that any ongoing source of mercury can be shut off.

Grant Walsom heads the Remediation and Risk Assessment Business Group at XCG Consulting and is vice-president of the Canadian Brownfields Network. He has over 20 years’ experience in soil and groundwater remediation, mostly at industrial sites. Walsom agreed that if the river has not recovered on its own after all this time, there is likely an ongoing, low-level contaminant source. “One possibility is that there could be groundwater carrying mercury into the river at certain times of year—whether it’s from the chlor-alkali plant site, a disposal site, or something else,” said Walsom.

Nor was Walsom entirely surprised by Earthroots’ findings. “There were a lot of poor disposal practices in the 60s and 70s,” he said. “It was very common for people to just dump waste or solvent in the gravel area behind the plant to kill the weeds, or to just dig a hole and bury it.”

If, however, it turns out that the mercury is coming from sediments in the Wabigoon River between Dryden and Clay Lake, the situation will be trickier to address. Rudd said that if additional fieldwork reveals hot spots where mercury concentrations are particularly high, remediation solutions might include some very localized hydraulic dredging and/or armoured capping—capping involves adding materials to cover contaminated sediment to prevent it from entering the water column.

Cleaning up Clay Lake

To deal with the mercury present in the lakes and rivers, Rudd and his team ranked a number of options according to what would be most effective, least disruptive to the environment, and least costly. This led them to ENR and nitrate injection at Clay Lake.

It is important to understand that methyl mercury, the form of mercury found in fish, is produced from inorganic mercury, either in the sediments or in anoxic (low-oxygen) bottom waters of lakes by bacteria that live there. The methyl mercury then moves up the food chain into the fish.

With ENR, the idea is to dilute the concentration of inorganic mercury in the sediments by adding clean sediments taken from another part of the river system. “If you could increase the clean sediment load to Clay Lake by a factor of two, mercury concentrations in the lake would be half, and so methylmercury production would be half,” said Rudd.

The second method proposed is to inject nitrate into the lake bottom waters to prevent the bacteria from producing methyl mercury. “Lakes with anoxic bottom waters often have higher mercury concentrations in the fish,” said Rudd. “We now know this is because […]the methyl mercury is produced right in the water itself. When that water mixes into the rest of the lake, the methyl mercury is immediately available to the food chain and goes right into the fish.” He added that nitrate injection has been shown to cause a quick reduction in mercury levels.

The report team estimated it would cost $6 million per year for ENR, which would need to be continued for seven to nine years; figures were not provided for nitrate injection.

Walsom thought the report and remediation solutions proposed were the least disruptive options. He also agreed with the proposal’s adaptive management approach, i.e. start with one solution, monitor and assess how it goes, then adjust the program accordingly.

Judy Da Silva, who grew up in Grassy Narrows when the chemical plant was still operating, has been living with the effects of mercury poisoning all her life. These include loss of muscle co-ordination, vision loss, and slurred speech. A leading advocate for her community, Da Silva hopes the backing of professionals like Rudd will help move things forward. But she is wary. She fears the fieldwork will just lead to another report that will sit on another shelf.

No remediation money promised

Last November, the Ontario government earmarked $300,000 for her community to continue its studies. About $80,000 has been received for work completed in the fall and for the next leg of fieldwork planned. So far, no money has been promised for actual remediation. “I feel like the government is stalling,” said Da Silva.

However, in a statement released February 13, 2017, the Ontario government said it is “committed to working with all partners [. . .] to creating and implementing a comprehensive remediation action plan for the English Wabigoon River.” The statement was signed by David Zimmer, Minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation, and Glen Murray, Minister of the Environment and Climate Change. The release also said that in light of new information that has come forward, “we are now conducting a full and rigorous mercury contamination assessment on the entire mill site.”

Rudd and his team are going back to Grassy Narrows this summer to try and identify the source of the incoming mercury, whether it’s from the plant or in the sediment. They will conduct further testing of ENR and nitrate injection to make sure these are the most appropriate remediation strategies for the area.

Rudd is optimistic. He plans to engage and mentor Grassy Narrows youth in the necessary fieldwork. “They will be involved in important parts of the scientific fieldwork, including the sampling of young walleye and northern pike.”

“Our youth will benefit from being exposed to the science of the river system,” agreed Da Silva. “The health of the river is the health of our people, the Anishinabek.”

Even if all goes well, Rudd estimated it will take at least five years from the start of remediation before mercury concentrations start to drop. A study of Clay Lake in 1994 found mercury concentrations were 2.4 ppm in walleye and 1.5 ppm in northern pike. A level of 0.5 ppm would allow commercial and sport fisheries to resume, but “for a sustainable fishery, it needs to be around 0.2 ppm,” said Rudd.

That is the ultimate goal for the Grassy Narrows people. “The food from the land is a part of who we are,” said Da Silva.