How often do you find yourself engaging in deep dialogue about systems with acquaintances, colleagues, or clients? When engaging in systems talk, we often notice people quit before the topic gets too complex. Systems are inherently interconnected and complex, which can be intimidating. What is more intimidating is seeing ourselves embedded in this complexity. To think through how systems manifest, interact, and are co- and interdependent is no small feat.

Marilyn Hamilton from Integral Cities described systems as being A-B-C:

- A is for anthropocentric systems or human systems (studied through psychology, sociology, and anthropology);

- B is for biological systems, which contain the living environment and life (studied through microbiology, biology, botany, and zoology); and

- C is for cosmosphere, which contains the universe, earth, and matter (studied through astronomy, cosmology, geology, and hydrology).

Hamilton explained that when we can see systems by recognizing their boundaries, we are practicing the basics of systems-thinking. When we can see how different systems are interconnected, we are progressing our systems-thinking to a more complex level. One such effort, especially in most recent years, has been to better understand the relationship between water and energy, which is often referred to as a nexus. This nexus is a perfect example of inter- and co-dependent systems (with food often included in the equation), but it’s not always given much thought by everyday citizens. The 2011 RBC Canadian Water Attitudes Study indicated that only 40 per cent of Canadians make the connection between water and electricity and 32 per cent don’t think about it at all. It often takes extreme weather events like a flood or a deep freeze for people to recognize how fragile and connected both water and energy systems are, especially in concentrated urban contexts.

Oddly enough, in an effort to synchronize the water-energy systems to each other, our planning has missed the mark on how to incorporate the human system to the water-energy conversation. Human systems are a collective of complex and organic functional relations, hierarchies, and processes that include both the individual and communal entities (such as family, community, neighbourhood, city, province, and country).

How can decision-makers and citizens collaborate to design more resilient Canadian cities, where water, energy, and human systems are well synchronized? Tony Hodgson, systems thinker and member of the International Futures Forum, explained that we need to plan for “transformative resilience.” Rather than figuring how to bounce back from disruption, how can we shift to a new system capable of absorbing and transforming to a new level of adaptive capacity? He further explained that this transformative resilience becomes possible through intelligent, humble, and scale-sensitive co-creation between human communities and the wider ecological communities they inhabit. For this we need a proactive approach where users and consumers who impact water and energy systems play a key role and are engaged at early stages in knowledge mobilization and strategic planning.

How can this be done?

Waterlution, for example, is embarking on a cross-Canada scenario-planning project called WaterCity 2040. The project is a nine-month process that will consist of five workshops in Toronto, Calgary, and Vancouver starting in fall 2014 to envision plausible futures for urban water systems and their management. These workshops will feature local city provocateurs to share innovative approaches that can inspire the direction of the scenarios. The scenario-planning process will be open to the public, offering cross-sector and intergenerational dialogue opportunities for more than 100 stakeholders from a variety of sectors in each city. The process will ultimately result in 25-year action reports to be considered by decision-makers.

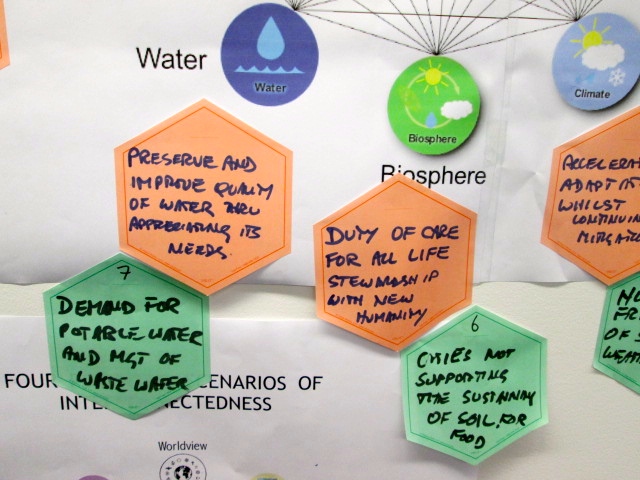

Another example took place on July 23, 2014 when Waterlution, the Canadian Water Network, OCAD University, and the Strategic Innovation and Foresight Lab at OCAD invited Tony Hodgson to Canada to facilitate his renowned World Game. This “game” is a creative form of engaging a variety of stakeholders to work on 12 systemic nodes (such as water, food, well-being, energy, climate, biosphere, governance). The central question of this workshop was: What should Toronto be doing to protect and develop its resilience in a world that is increasingly assailed by worrisome trends, shock events, and out-of-control complexity? Designers, consultants, urban planners, civil engineers, sustainability professionals, academics, members of the ministry of environment, and consulate representatives, to name a few stakeholders, were assigned roles as “chiefs” of each node. In small groups, they developed scenarios based on assessing relationships between their nodes, observing current and future trends, shock events, and complexities, and recommending policy changes. This game has been used by public health officials in Scotland, delta-cities research teams at UNESCO-IHE in the Netherlands, and companies assessing future trends worldwide—and now there is greater interest in bringing it back to Canada, to create future-focused action plans that inform policies on water-energy system resilience.

It is important to create more open spaces like the examples mentioned, where stakeholders can be invited to creatively collaborate and co-create together. We will be much more prepared when the value of foresight and scenario planning is brought deeper into systems thinking, especially around water-energy systems.

How can we can build transformative, resilient systems? Start with new and creative ways of engaging policymakers and the larger public with knowledge, recognize that the human system needs to be synchronized to other systems first, and use foresight in systems thinking to draw the connection between co- and interdependent systems.

Dona Geagea is an advisor to Waterlution with three years’ experience as Waterlution Hub Manager. Karen Kun is the co-founder and executive director of Waterlution.

SIDEBAR: Water-Energy Nexus By the Numbers

- About eight per cent of the global energy generation is used for pumping, treating, and transporting water to various consumers.

- The energy sector withdraws water at approximately the same rate that water flows down the Ganges or Mississippi rivers—two of the largest rivers in the world.

- It takes 100,000 gallons of water to produce a single megawatt hour of electricity

- Seventy per cent of global water use goes into the agriculture sector.

- As much as two billion tonnes of food are wasted every year—equivalent to 50 per cent of all food produced, according to a report published by the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. Think of the amount of water and energy wasted in the process.